Nobody Talks About Rick Anymore?

It’s a little-known fact that Warren Buffett and Charlie Munger had another partner back in the 1970s named Rick Guerin. Rick ran his own fund called Pacific Partners but worked with Munger and Buffett to gradually acquire a controlling interest in a company called Blue Chip Stamps.

Blue Chip Stamps was a small company that issued trading stamps that merchants like grocery stores distributed based on their sales, allowing customers to redeem for merchandise. These were the first “loyalty points” programs for a better comparison.

After acquiring Blue Chip Stamps, the three investors used the “float” of the company, which is the cash accumulated between the stamps issued and stamps collected, to fund other acquisitions. The main acquisition they then partnered on was See’s Candy in 1972 for $25 million. In fact, Munger, Buffett, and Guerin together interviewed Chuck Huggins to be the CEO of See’s Candy at that time.

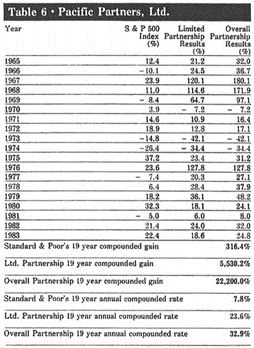

Buffett himself wrote about Rick Guerin in 1984 in his famous essay called “Superinvestors of Graham and Doddsville.” In this, he outlined famous value investors and their performance. Buffett included in the essay the following table, which summarized the performance of Rick’s fund Pacific Partners, Ltd.

As you can see, it had quite extraordinary performance relative to the S&P 500 over the 19 years. However, after having such rapid success working with Buffett and Munger, their paths diverged following the See’s Candy acquisition. Buffett and Munger became a two-man show, absent Rick Guerin.

So, why does nobody talk about Rick anymore? His results speak for themselves, but why isn’t he regarded with such reverence as Buffett and Munger? Stating the obvious, it’s because Buffett and Munger didn’t work with him anymore.

Buffett’s essay lacks details about their dissolved partnership after the wildly successful Blue Chip Stamps and See’s Candy purchases. Clearly, Guerin was very successful, earning a return of 22,200% from 1965-1983, so competence couldn’t be the reason? However, Guerin faded into the background in the 1980s, never working with Buffett or Munger again.

In 2008, enter Mohnish Pabrai. Pabrai, a money manager who ran Pabrai Investment Funds, was the winner of lunch with Warren Buffett after bidding more than $650,000 on eBay for a meal with him. Pabrai asked Buffett during lunch what had happened to Rick Guerin. In an interview with The Motley Fool on January 3rd, 2013, Pabrai had this to say about Buffett’s response to his question:

“I've met Rick recently, but he disappeared off the map, so I asked Warren, are you in touch with Rick, and what happened to Rick? And Warren said, yes, he's very much in touch with him. And he said, Charlie and I always knew that you would become incredibly wealthy. And he said, we were not in a hurry to get wealthy; we knew it would happen. He said, Rick was just as smart as us, but he was in a hurry. And so actually what happened -- some of this is public -- was that in the '73, '74 downturn, Rick was levered with margin loans. And the stock market went down almost 70% in those two years, and so he got margin calls out the yin-yang, and he sold his Berkshire stock to Warren. Warren actually said, I bought Rick's Berkshire stock at under $40 a piece, and so Rick was forced to sell shares at ... $40 apiece because he was levered. And then Warren went a step further. He said that if you're even a slightly above-average investor who spends less than they earn, over a lifetime, you cannot help but get rich if you are patient. ”

Looking back at the returns chart for Guerin’s Pacific Partners, you will see the drop in 1973 of 42%. Guerin followed up the drop in 1973 with another 34% drop in 1974. That would be a cumulative drop of almost 62% in two years. During that two-year period, the S&P 500 did drop more than 37%, but the 62% drop in Guerin’s fund was almost catastrophic. While he obviously recovered later, many investors and partners probably lost faith just as Buffett and Munger did.

Needless to say, the drop in his fund during 1973 and 1974 forced Guerin to sell back his Berkshire Hathaway to Buffett at the $40 level to cover margin calls and losses. Those shares would be worth $430,000 each at the time of this writing. As Buffett noted in his conversation with Pabrai, it was the leverage that forced the sale and exacerbated losses in his portfolio partnership. This violates a key axiom of investing: sell equities when you want to and not when you have to.

Aside from the monetary losses, it seems that the use of leverage also lost Guerin the faith and trust of Buffett and Munger. Guerin’s long-term documented results are quite amazing, but he lives on in obscurity. He could have been legendary, but his “impatience” cost him the chance at being on the Mount Rushmore of investing.

What can we learn from this? Even though this happened decades ago, the old axioms of greed and “impatience” live on daily in the markets. Crypto assets, meme stocks, and startup companies have seemingly made millionaires overnight. Couple these stories with the virality of social media, and your “inbox” seems full of folks getting rich with seemingly little effort. This breeds impatience and causes investors to do irrational things to try and “catch up.” Taking too much risk, using leverage and margin, get-rich-quick schemes, and concentrating assets instead of diversifying risk are all symptoms of impatience.

We live in a society that continues to promote immediate gratification, but sometimes to be a great investor, you need patience and time. As Buffett noted, “Even a slightly above-average investor who spends less than they earn, over a lifetime, you cannot help but get rich if you are patient.”

Perhaps even more importantly, you need to invest in a way that doesn’t force you to sell at an inopportune time (ex., because of a margin call or other catastrophic event that makes you sell for liquidity needs). That is the key to owning equities and maintaining your patience to let the markets reward you. If you have any questions about this article, please contact us.

- Analytical, Strategic, Consistency, Includer, Input

Justin Vossen, CFP®

Justin Vossen, Investment Advisor and Principal, began his career in 1997. With extensive experience in finance, banking, and investment management, he brings comprehensive expertise to his role advising high-net-worth clients and foundations. As a member of the Lutz Financial Board his leadership extends beyond client relationships to shaping the firm's direction.

Leveraging his background in bond trading and portfolio management, Justin focuses on providing comprehensive investment and planning services. He develops tailored financial strategies across wealth management, retirement planning, and estate planning. Justin values creating solutions that give clients peace of mind about their financial situations.

At Lutz, Justin establishes unshakeable trust through his analytical mindset and strategic approach to investment management. He takes time to understand what truly matters to each client—whether it's retiring early or successfully transferring a business—and then builds comprehensive financial strategies to help them get there.

Justin lives in Omaha, NE. Outside the office, he can be found spending time with his wife, Nicole, and their children, Max and Kate.

Recent News & Insights

Do You Need a Family Office? 7 Aspects to Consider

Tariff Volatility + 4.7.25

Lutz Named Top Consulting Firm in 2025 Omaha B2B Awards

Direct vs. Indirect Costs in the Construction Industry

.jpg?width=300&height=175&name=Mega%20Menu%20Image%20(1).jpg)

%20(1).jpg?width=300&height=175&name=Mega%20Menu%20Image%20(2)%20(1).jpg)

%20(1)-Mar-08-2024-09-27-14-7268-PM.jpg?width=300&height=175&name=Untitled%20design%20(6)%20(1)-Mar-08-2024-09-27-14-7268-PM.jpg)

%20(1)-Mar-08-2024-09-11-30-0067-PM.jpg?width=300&height=175&name=Untitled%20design%20(3)%20(1)-Mar-08-2024-09-11-30-0067-PM.jpg)

%20(1).jpg?width=300&height=175&name=Mega%20Menu%20Image%20(3)%20(1).jpg)

%20(1).jpg?width=300&height=175&name=Mega%20Menu%20Image%20(4)%20(1).jpg)

%20(1).jpg?width=300&height=175&name=Mega%20Menu%20Image%20(5)%20(1).jpg)

-Mar-08-2024-08-50-35-9527-PM.png?width=300&height=175&name=Untitled%20design%20(1)-Mar-08-2024-08-50-35-9527-PM.png)

.jpg)